Here is a blog post written specifically for your audience at My Core Pick.

Make Your Low End Punch: Unmasking the Kick and Bass with Dynamic EQ

We have all been there.

You spend hours crafting the perfect loop. The kick drums are thumping, and the bass line is groovy. It sounds massive in your head.

Then, you bounce the track and listen in the car.

Suddenly, that power is gone. The low end sounds like a muddy, indistinct blob. You can’t tell where the kick ends and the bass begins.

This is the most common struggle in mixing: the battle for the low frequencies.

It’s frustrating, but it isn't unfixable.

For years, I tried to solve this with standard static EQ. I would carve out huge chunks of my bass guitar, only to find it sounded thin when the drums stopped playing.

Then I discovered the power of Dynamic EQ.

Today, at My Core Pick, I’m going to walk you through exactly how to unmask your low end. We are going to make that kick and bass relationship tight, punchy, and professional.

The War Down Under: Why Mud Happens

Before we start turning knobs, we need to understand the physics of the problem.

The low end of the frequency spectrum (20Hz to 250Hz) is prime real estate. It is also incredibly small.

You have huge wavelengths carrying a lot of energy, all fighting for very limited space.

The Concept of Masking

When two instruments occupy the same frequency range at the same time, the louder one tends to hide the quieter one.

This is called "frequency masking."

In most modern genres, the fundamental frequency of your kick drum usually sits between 50Hz and 80Hz.

Guess where the heavy body of your bass line sits? Usually right between 50Hz and 100Hz.

They are essentially roommates trying to walk through a narrow door at the exact same time. They get stuck, and nobody moves forward efficiently.

The Problem with Static EQ

The old-school method was simple subtraction.

If the kick is hitting at 60Hz, you would grab an EQ on the bass channel and cut 60Hz by 3dB or 6dB.

This works to clear up space, but it comes at a cost.

A standard EQ is "static." That cut is active 100% of the time, regardless of whether the kick is playing or not.

So, when the kick drum hits, the mix sounds clean.

But in the sections between the kick hits, or during a breakdown where the drums drop out, your bass line is now permanently thin. It lacks body because you hollowed it out.

We want the best of both worlds. We want the bass to be full and rich, but we want it to "duck" out of the way only when the kick demands the space.

Dynamic EQ: The Smart Solution

This is where Dynamic EQ changes the game.

Think of Dynamic EQ as a marriage between a compressor and an equalizer.

It allows you to boost or cut specific frequencies, but—and this is the magic part—only when the signal crosses a certain threshold.

It reacts to the music. It breathes with the track.

Why Not Just Use Sidechain Compression?

You might be asking, "Why not just use standard sidechain compression on the whole bass track?"

Standard sidechain compression turns the volume of the entire bass track down every time the kick hits.

This creates that famous "pumping" sound found in House and EDM.

That is great if you want that artistic pumping effect.

But what if you are mixing Rock, Jazz, or Pop? You don't want the high notes of the bass guitar to disappear every time the drummer hits the kick.

You only want to clear the mud.

Dynamic EQ allows you to surgically duck only the colliding frequencies (say, 60Hz) while leaving the mid-range and treble of the bass perfectly intact.

It is transparent. It is invisible. And it makes your low end punch like a heavyweight.

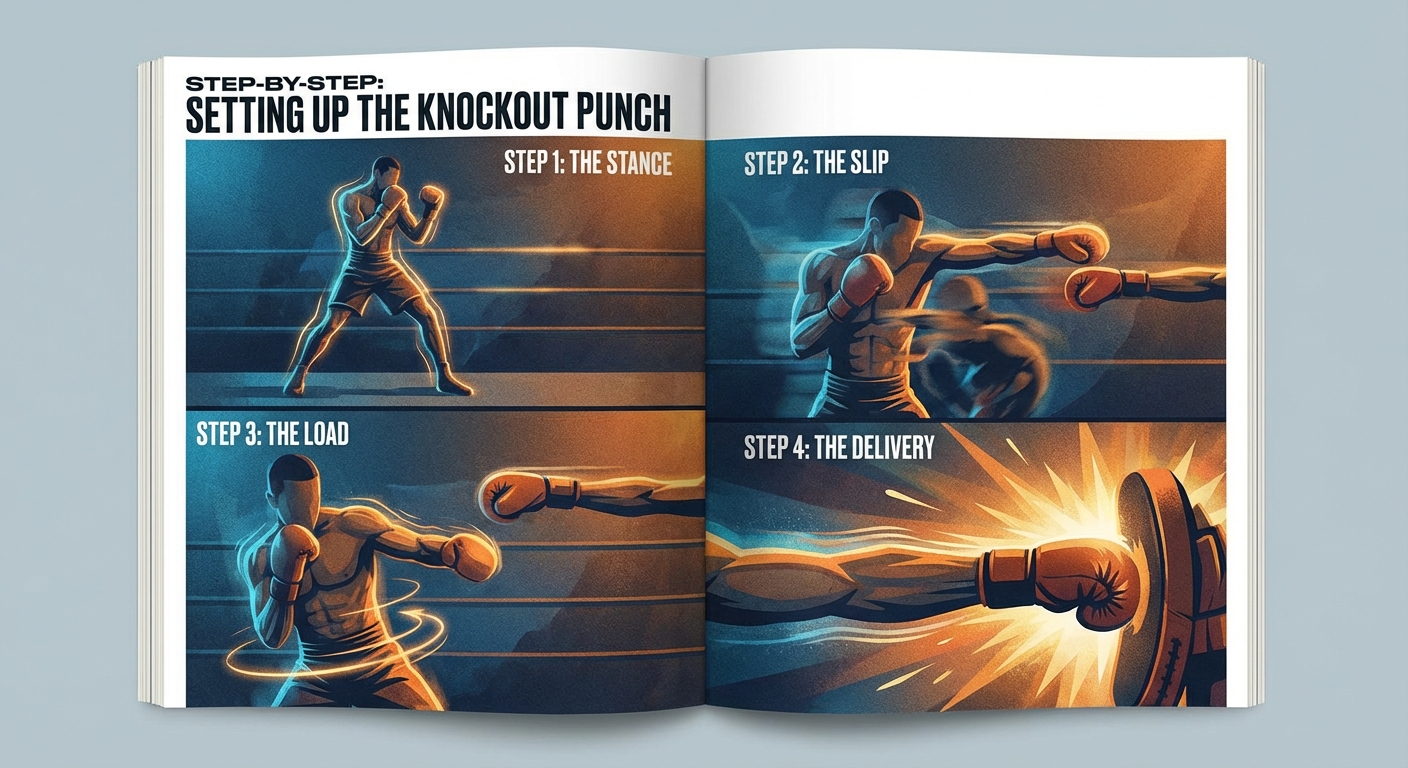

Step-by-Step: Setting Up the Knockout Punch

Let’s get into the practical workflow. I’m going to break down exactly how I set this up in a mix.

You will need a Dynamic EQ plugin that supports an external sidechain input. (Most modern pro EQs do this now).

Step 1: Identify the Clash

First, put a spectrum analyzer on your master bus, or look at the analyzers on your individual tracks.

Solo the kick drum. Look for the fundamental peak. Let’s say it is hitting hard at 60Hz.

Now, solo the bass. Look at where its energy is focused. If it is also heavy at 60Hz, you have found your conflict zone.

Step 2: Route the Signal

On your bass track, load up your Dynamic EQ.

You need to tell the EQ to listen to the kick drum.

Route a send from your Kick track into the "Sidechain Input" (or Key Input) of the Dynamic EQ on your bass channel.

We aren't sending audio to be heard; we are sending a trigger signal.

Step 3: Create the Dynamic Node

On the bass EQ, create a bell filter at 60Hz (or wherever that kick fundamental was).

Instead of pulling the gain down manually, leave it at 0dB.

Engage the "Dynamic" mode on that band.

Set the source of the dynamic band to "External" or "Sidechain."

Step 4: Dial in the Threshold and Range

Now, play the track with both kick and bass running.

Lower the Threshold on that band until you see the gain reduction meter start to move every time the kick hits.

You want the EQ to dip down (cut) only when the kick strikes.

Adjust the Range (or Ratio) to determine how deep the cut is. I usually aim for -3dB to -6dB of reduction.

Listen closely. You should hear the kick drum suddenly "pop" through the mix. It will feel like it has more impact, but you haven't actually turned the kick up.

You’ve simply removed the obstacle standing in its way.

Refining the Groove: Attack and Release

Getting the cut to happen is only half the battle.

To make it sound natural, you need to massage the timing.

If the timing is off, the low end will sound jittery or nervous.

The Attack Time

For a kick and bass relationship, you generally want a fast attack.

The low end of a kick drum happens almost instantly. You want the bass to get out of the way immediately.

If the attack is too slow, the initial transient of the kick will still clash with the bass before the EQ clamps down.

Start with an attack time around 10ms or faster.

The Release Time

This is where the groove lives.

If the release is too fast, the bass volume will snap back up too quickly. This can create a weird, audible fluttering sound (distortion) in the low frequencies.

If the release is too slow, the bass stays quiet for too long, and you lose the power of the bass line between kick hits.

You want to time the release to the tempo of the track.

I usually aim for a release that lets the bass return to full volume just before the next musical subdivision (like the next 8th note).

Trust your ears here. Close your eyes and listen to the interplay. It should feel like the bass is "dancing" with the kick, not getting strangled by it.

Advanced Techniques for Clarity

Once you have the fundamental frequency sidechained, you can take it a step further.

Here are a few advanced tricks I use at My Core Pick to get that final 10% of polish.

The Inverse Relationship

Sometimes, masking isn't just about the sub-lows. It happens in the upper harmonics too.

The "click" or "beater" sound of the kick helps it cut through small speakers (like phones). This usually lives around 2kHz to 4kHz.

Sometimes the bass guitar has a lot of string noise in that same area.

You can use Dynamic EQ here too. Duck the high-mids of the bass slightly when the kick hits.

Alternatively, you can do the opposite.

If you want the bass line to growl more when the kick hits, you can set a dynamic boost on the bass's upper harmonics that triggers when the kick hits.

Checking Phase Alignment

Dynamic EQ is transparent, but any EQ changes phase.

Always double-check your kick and bass in mono after applying these changes.

Flip the polarity (phase) on the kick drum channel while listening to them together.

Choose the polarity setting that provides the most solid, centered low end.

Don't Forget the High Pass

Dynamic EQ is powerful, but don't forget the basics.

Your bass track probably doesn't need anything below 30Hz. That is just rumble that eats up headroom.

Your kick might not need it either, depending on the genre.

Using a static High Pass Filter on both tracks to clean up the sub-30Hz rumble will make your Dynamic EQ work even better.

It prevents the compressor circuit from reacting to invisible energy.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Before you go apply this to every track in your session, let’s cover a few pitfalls.

It is easy to get carried away with visual mixing.

Mistake 1: Listening in Solo

Do not dial in your Dynamic EQ settings while listening to the bass in solo.

You cannot hear if the masking is being resolved if you aren't listening to the kick and bass together.

In fact, I recommend checking the effect while the whole mix is playing.

Does the low end feel anchored? Does the kick punch through the wall of guitars and synths?

Mistake 2: Over-Ducking

You don't need to cut 12dB out of the bass.

If you cut too much, the bass will sound like it is hiccuping.

We are looking for clarity, not a special effect. Subtlety is key.

Often, a reduction of 2dB to 4dB is all you need to trick the ear into hearing separation.

Mistake 3: Wrong Frequency

Make sure you are ducking the fundamental of the kick, not the fundamental of the bass.

We are carving a hole for the kick.

So the frequency center of your EQ band should match the kick drum's pitch, not necessarily the bass note.

Conclusion

The relationship between the kick and the bass is the heartbeat of your track.

When they fight, the listener feels fatigued. The mix feels amateur.

When they work together, the track feels expensive, punchy, and energetic.

Dynamic EQ is the peace treaty that allows these two giants to coexist.

By setting up a sidechain dynamic band, you ensure that the kick gets the spotlight for the split second it needs it, and the bass keeps its body for the rest of the time.

It retains the musicality of the performance while solving the technical issues of physics.

Open up your latest session. Find that clash. Set up your Dynamic EQ.

You will be amazed at how much headroom you suddenly recover and how much harder your drop hits.

Keep experimenting, and keep your low end clean.

Catch you in the next post,

The My Core Pick Team